|

Chapter 1

Roots of Madiga identity (2)

Exploring further among the roots

The first part of this chapter has presented some recent evidence

for Madiga thinking on the roots of their identity. There have also been glimpses of other aspects of the Madiga heritage

which will be explored in the chapters that follow. Much of this recently performed narrative wears an air of antiquity, in

content and in the style of its delivery, that may surprise. The India in which it is found is in the midst of globalisation.

Hyderabad with its HiTec City, the great metro and IT hub, its buildings rising ever higher, is only two hours away on the

busy National Highway from our villages. Indeed the heritage penetrates the city itself in ways that are

also to be explored. The key texts that follow immediately begin to reveal the historical depth and the range of variation

over time and space across the vast region of peninsular South India that has been the home of Madigas for centuries past.

a) Jāmbavanta

‘Jambava’ was the simple form chosen in the first part of this chapter for the name of the Madiga first ancestor.

Easily recognisable variations of the same name are numerous, and quite different names equated with them appear too: Burabatta

and Zalazam will be found below. Comparison will show how individual versions of the origin myths are woven out of the immense

imaginative resources of names and events generated within the sub-continental civilisation. They allow an unending flood

of meaningful narratives to emerge over the centuries.

Mackenzie

Collection Parayans and Madigas, Vol. 23, Item 35 of Vol. 1, Pt 2, Catalogue of Manuscripts in European Languages

belonging to the Library of the India Office, London: British Library 1992

The earliest direct and contemporary record of Madigas that has yet been found comes only from the end of

the 18th century. It comes from a survey of the border area that is now mainly the Dharmapuri and Salem districts of northern

Tamil Nadu. This was directed by a Scottish officer, Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1754-1821) who was later Surveyor General of

India. His collections provided a major impetus for research in the 19th century and for the long series of ethnographic surveys

and gazetteers that now offer important sources of later evidence.

In this region the Madigas (‘Maudigawaru’) were divided into Telugu (‘Telinga’) and Kannada

sections, but also linked as leather workers with ‘Arva Chucklers’, i.e. Tamil Chakkiliyars. They shared, it was

said, the same customs and could eat together but they would not intermarry. The tutelary deity of the Telugus was said to

be God Brahma. They also gave ‘adoration to a Satyr named Jambawont’, but neither had temples.(d) The Tamils on the other hand were said to be ‘all Vishnu Bukt’

and to be attached to God ‘Narasimhaswamy at Cudry in Mysore’.

(e) A Brahmin, Cadry Lingaraiah, was their guru but he deputed a man of Dasari caste who gave them ‘Namon and Tirtha

Praddha or Holy water and consecrated flowers’. In return they paid annually ‘2 Dubs, a small copper coin, from

each house’ to the Dasari and provided eatables for him when he visited. The Dasari passed on his collections to the

guru.

It was probably

from this non-Madiga source that an interesting variant of the widely known story outlined above comes. This is about the

bringing together of Madigas and Malas – or in this largely Tamil context Paraiyars – in a fateful eating of beef.

[p. 348]

In former times, a person of the Parriar cast kept the cows of

the God Brahma. One day the God’s consort, the Goddess Saraswati, put by a pot of milk which became covered with cream.

The Parriar availing himself of an opportunity tasted the cream, which he found very palatable and thought that if the milk

was so good, the flesh of the cow must be much better, and to make the experiment, he killed one of them when out to graze.

At night when the cows were brought home, one of them was missing, and the God by the strength of his prophetic endowments,

perceived the trick, and as a punishment commanded the Parriar to feed on the flesh. But he humbly suggested, that there was

too much for him and begged he might have an assistant to help him to eat it. On which, the God rubbed the sweat off from

his arm and dashed it on the ground when a human being spring up into existence, whom he named Maudigawaru and directed him

to assist the Parriar in eating the flesh of the cow.

This

early account is interesting in several ways. It is far simpler and more naturalistic. The ‘person of the Parriar cast’,

the ‘Chennaiah’ of this version, is made the actual slaughterer of a cow rather than indirectly responsible for

the death of the miraculous Kamadhenu.

Then it is Brahma and Saraswati, as well as the Parriar, who initiate the story that will result in the creation of ‘Maudigarawaru’;

no Jambava is placed ahead of them in the narrative of creation. The link with Brahma is however impressively close and the

very reason for Maudigawaru’s creation is the disposal of the flesh of the cow. Though this Brahmanical idea may not

have come from a Madiga source, as a line of thought it has also been recorded from one. A CMS missionary at the port of Machilipatnam

in Krishna district in the mid 19th century records with amusement a conversation with a Madiga: ‘One man said quite

seriously, “But if we all turn Christians, what will become of the dead cattle?” For the Chucklers are the privileged

consumers of all bullocks, cows, and buffaloes which die of disease or old age. “ Suppose”, he added, “some

of us join your religion, and we will leave some behind to eat the cattle”’ (Fox 1850, p. 255).

Walter Elliott, 19th century. ‘Aboriginal Caste Book’, a compilation of reports

and cuttings made in South India in 3 vols and included in the Johnston Papers in the British Library. (f)

The narrative told here, presumably for legal purposes, closely

resembles a kula purana or caste myth in form and in content. It shares much with the performance version from Telangana but

differs in linking Jambava into one of the major epic cycles of the region rather than with the Yellamma cult. Nevertheless,

here ‘Búrrabatta Ellamma’ is worshipped in Warangal. ‘Burabutta’ – who is to become Jambava

in this account – is here a general and the supporter of kings, instead of the wise and holy muni , supporter

of gods, seen above. The Yellamma link is considered further in Chapter 3.

[p. 570-71]

There existed neither the atmosphere nor the earth. The points of the

compass were originally in existence. They created Sakti (14) or the female energy because the world could not get on without

her. When Sakti attained her puberty in their world she conceived (15) and was happy – and performed a penance

in a retired place. Leaning on one side, she laid three eggs from her three eyes. Twelve months afterwards, a certain Guru(16)

groaned and came out of one of them. Sakti having seen the two other Eggs, kicked one of them with her foot & broke it.

Vishnu, Iswara, and Brahma were born as brothers. Then Sakti made these three deities, lords of the three worlds. Sakti again

kicked the remaining Egg and broke it. The earth was produced from it in the shape of Nundi or Bull, and the atmosphere in

the form of Madi(17). The sun and the moon were the eyes of Vishnu. Brahmins were produced from the face of Brahma; Kings

from his arms; Vaisyas from his breast, & the race of the Súdrás from his feet. Búrábutta

was produced from the yaning or gaping of Brahma, and adored Sakti.

The four person Viz Ráma, Lakshmana,

Bharata & Satvighna were the sons of Dasaratha. Ráma was the son in law of Dunaka(18),

by marrying Síta – and returned to Ayodhya and adored Sakti. In the days of Ráma, he (Búrábutta)

was called Jambuvanta because he obtained the blowing horn called Jambuvanta which belonged to Sakti. He was a warrior equal

to Lanka Raya Bhavanta or Rávana. Jambuvanta and Hanumán, conquered Lanka Ráya Bhavanta. The residency

of Jámbuvanta was a bush at Elaváda. The descendants of Jámbuvanta are Gamantídu, Mástídu,

Gosangi Bantu(g), Aranjóti, Kali, and Ganti (h). They are

six in number. One of the descendants of Jámbuvanta rode on a buffaloe(19).

Panchapándavás – the lords of eight quarters; and Hari and

Hari [sic] came for the marriage of Arundhati and Vasista. During the marriage 12 copper pillars were fixed – and a

golden Panjaram or cage was placed in the middle of them with a golden Badge or Birad called Pinára. Aranjóti

came riding in a palanqueen which was brought by Vasista accompanied by drums and tabours. In this mortal world, Swāmi

gave presents of bell, Dhappu or Drum, Nisháni or flag & a horse. They adored the goddess Alabeta on the sea shore.

The universe existed on the points of ploughshare (20) - of an Iron style or pen – of the spindle of a spinning wheel

& of the shoemakers awl. The pair of bellows (21) which were presented to Chelluri Siva Bhatta, were very useful for the world. Viswakarma (22) presented Gosangi with a Ranakatti or war sword. It was of the hight [sic] of seven palm trees placed one over

another – and so heavy as to require ten carts to carry it.

[Episodes

of the Katamarazu epic follow at length here, eventually reaching Oragal, the Kakatiya capital and the modern city of Warangal

in Telangana. See Rao and Shulman 2002.]

[p. 575-58:]

In the City of Oragal, they adored Búrrabatta Ellamma

with strings of Cowries & of margosa leaves. They blowed double & single horns & beat Víranams & Jamilika.(i)

At that time, Párvaty & Paraméswara went to the

forest, Pamba became menstruous in her own lodgings. Mala was born from a cloth stained with menses, because he would eat

cows. Afterwards the unclean Mala who was born from the cloth with menses, was (one day) grazing the cows on the mountain

of Sanjivi. At that time Hari & other celestials as well as Panchapándavas, came to the house of Siva to pay him

a visit. Siva served them with Paramanna (rice with milk and sugar). At that time, Mala came & a portion of Paramanna

was given to him. He ate it and said ‘oh, this is an excellent food. How delicious will it be if I eat the cow’.

So, he killed a cow. Siva asked the Mala where is the cow? He answered that he did not know where she was. Then Siva, pronouncing

a few mystical words over the ashes, produced a jackal & wolf, & sent them to discover the traces of the cow. On ascertaining

her fate, Vishnu, Brahma, Dévatas, & Panchapandavas, came and saw the (dead) cow.

Then Iśwara, desired the celestials, to allow the carcase to be taken into Kailasa and Vaikuntha.

They said that they could not permit her carcase to be taken into Kailása & that if Búrabatta be called

for, he will be able to explain the mystery. Then the 3 crores of celestials called out Mahadigi(23) or Come down you great man! He accordingly came down

from Sinha ghanta, & asked Siva why they called him. He desired him to admit the cow which was killed by the Chandála

into Kailása. Then the Chandála was permitted to hold the died cow & Burabatta himself cut her to pieces.

With a desire that the flesh may not be polluted by being put in the Malas pot & by being boiled on his hearth, Burabatta

distributed it while it was raw, to the Panchakóti Pandavas. As the Mala has committed the said wicked act, he cursed

him in the following words. ‘As you have committed this wicked(24) act, you shall have in your possession food barely sufficient for three months, & borrow provisions

for your maintenance during six months in a year – your light shall be that of the burning sticks – you shall

drink your Canje or broth in a pot(25).

After Rama departed this life, temples were built in his honor. Púsapáti MalaRaja was crowned.

They all entered Vijaya Nagaram. Burabatta became servant of the Maharaja. The Ganges at Kási sanctified the world.

Maramudi(j), the servant of Maharáj, took the measurement

of the 7 worlds below [?] worlds above & went to Conjevaram. Cancivarada being pleased with his measurement, gave him

the name of Gósangi and presented him a horse & cloths. He likewise gave him this Dharma sásanam, telling

him at the same time that he was an old & (faithful) warrior. This was on a pillar at Conjevaram – persons denying

its existence shall incur the guilt of having killed a cow at Cási [sic].

Gosangi Bantoos (k);

Masterloo, Sindhus, & Dackuluvadu are the subjects of the Mahanad.

Velmas, gollas, Kamma’s, gurava Kammas,

held a meeting near Pancha Dhára.

At that time, zemindaries were granted to the Rájas. A pair of bellows

were given to the

Kamsalies or goldsmiths – A sidde or leather bottle to gaura Komaties – a case of

knives to Madas or Toddy drawers – a case of razers to the Barber – a piece of skin to the

potter –

A bow to the Cotton Cleaner. All these were given for conducting the business

of the Mahanad who (in return) gave to

Gosangi Bantoo flesh and liquor with a present of

horse and cloth.

b) Aranzodi (Arundhati)

(l)

If much of the lore of Jambava belongs exclusively to Madigas, Aranzodi or, in its Sanskrit form Arundhati,

is located in the classic literate traditions, developed in major puranas, through her marriage to the Rig-Vedic Rishi Vasiṣṭha.

They are seen as two stars in the sky: ‘chaste Arundhati has resorted to the excellent muni Vasiṣṭha’.

She is the exemplar of the chaste and faithful Hindu wife, rivalling even her husband in her performance of tapas

(austerities) (Mitchiner 1983, pp 43, 237-9 and passim). Madiga perspectives relate to the classic narratives in a variety

of ways.(m)

Emma Rauschenbusch-Clough 1899. While Sewing Sandals. Or Tales of a Telugu Pariah Tribe.

London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Emma Rauschenbusch-Clough reports from Ongole in coastal Andhra

at the end of the 19th century. See preceding section.

[pp 53-56]

There

was once upon a time a Brahmin who had done many evil deeds. He believed that he could receive the expiation of all his sins

if he found a woman who had faith sufficient to transform sand into rice. He inquired among all castes, but nowhere was there

a woman who had this supernatural power.

Finally he came to the Madigas. Now the maiden Arunzodi heard of his quest. She

appeared before him and said ‘I can do it, but I am of low birth. My father is wont to kill cows and eat them. We are

outcasts.’

The Brahmin was exceedingly glad, and he besought the maiden to grant his request, notwithstanding

her low degree. He argued with her, but Arunzodi said, 'When my elder brother comes home and sees you, his wrath will

be great, for we eat meat.'

This did not convince the Brahmin; he insisted,

and finally Arunzodi yielded. He brought sand and she put it into the pot. He broke iron into small pieces, and this also

she put into a pot. She saw what she had in the two pots, but so great was her faith, she proceeded to boil it.

With great anxiety the Brahmin stood by and watched. When Arunzodi had finished cooking, behold! one

of the pots contained boiled rice, the other was full of curry. Certain that he had found his saviour, the Brahmin asked for

Arunzodi in marriage.

But now the elder brother came home. He was enraged when he

heard what had happened, and threatened to do violence to the Brahmin and to Arunzodi, his sister, also. No one among the

Madigas befriended them, for all said: 'She is bringing a stranger into our households and our caste! Turn them out! Away

with them!'

Then it was that Arunzodi, before the eyes of all, rose

to heaven. And she cursed them, saying: 'You shall be slaves of all. Though you work and toil, it shall not raise your

condition. Unclothed and untaught you shall be, ignorant and despised from henceforth!' Thus Arunzodi cursed her people

as she rose up, and they and the Brahmin were left standing and gazing after her.

The Madigas cannot forget Arunzodi. The

Dasulu often tell the story of her faith, and of the curse with which she cursed her people, which, alas! has been fulfilled.

And as the Dasulu recite they accompany themselves with instruments. There are other legends about Arundhati, which is the Sanscrit form of the Telugu word Arunzodi, and means ‘everlasting

light.’ One is that Arundhati was re-born as a Madiga woman, and married the sage Vasishta, the brother of the great

Agastya. She bore him one hundred sons, ninety-six of whom reverted to the Pariah state, because they disobeyed their father,

while the other four remained Brahmins. Among the hymns of the Rig Veda there is a bridal hymn. At the close this verse occurs:

‘As Anusuya is to Atri, as Arundhati to Vasishta, as Sati to Kausika, so be thou to thy husband.’ It is significant

that in Sanscrit dictionaries both Arundhati and Matangi are mentioned as the ‘wife of Vasishta,’ making the two

identical.

When they have a wedding, the Madigas specially remember Arunzodi. After one of the Madiga Dasulu

has performed the marriage rites, as ancient custom demands, it is thought well for the prosperity of bride and bridegroom

if they, accompanied by their friends, go out under the starlit heaven to greet Arunzodi. Though she may not be visible, her

cot is always there, and all can find it. The four bright stars in Ursa Major are the feet of her cot, made of very precious

material. The three stars on one side of the four are thieves, who are stealing three feet of the cot, and have already pulled

the cot crooked, for the four feet form an irregular square. And so the young couple look at the cot, and say, ‘ Arunzodi

cannot be far away!’ They bow and worship, for they believe that she has power to bless.

Wilber Theodore Elmore, 1915. Dravidian Gods in Modern Hinduism.

A study of the local and village deities of Southern India. Hamilton, NY: The Author

In this great compendium of myths and rituals particularly concerned with Brahmin-Dravidian interaction, by an American

Baptist missionary at Ramapatnam, Nellore, from 1900 to 1915, an account of the same initial miracle is found. Both the context

and the significant detail are developed differently however. His field research was carried out mainly between 1911 and 1913,

after academic studies at the Department of Political Science and Sociology, University of Nebraska. General credit is given

to Mocherla Robert ‘through whose untiring efforts a considerable portion of the material has been secured’.

[pp 16-18]

The story commonly known

among the people runs thus. There was once a woman of high birth who married, but remained with her parents. One night her

husband came unannounced and lay down beside her. She did not recognize him and kicked him. Her husband then cursed her and

said that she should be born a Madiga. When her father heard of the matter, he called a great council of kings, and as a result

the son-in-law was cursed because he had not recognized the virtuous act of his wife. The curse pronounced was that he should

be born the son of a prostitute.

In process of time the two curses were fulfilled. Aranjothi was born a Madiga woman.

At that time there was a guruvu named Visva Brahma [see Chapter 3b]. His worshipers came to him and said, ‘You are always away on

your pilgrimages, so make us an image of yourself which we may worship when you are not here.’ He agreed, and a five-faced

image was made. It was decided that the image must have a wife, so a prostitute was brought and placed before it. By continually

looking at her the image caused her to bear a son. This boy was the reincarnated husband of Aranjothi.

The

people now told the boy that it was proper for one of such birth to go to heaven. He replied that he would not go unless they

worshipped him. They said that if he would take sand for rice, and small pieces of iron for puppu [pulses] and making

curry from these, would eat the food from the tiny jammi leaf, they would worship him.

The boy took the

sand and iron and traversed the entire earth attempting to find a woman who could fulfil the seemingly impossible conditions.

At last he came to the Madiga hamlet where Aranjothi lived. She was at that time worshiping Siva. She heard his request and

performed the feat. From the sand and iron she prepared a good rice and curry, serving it on the jammi leaves which

she had deftly woven together.

The man now asked Aranjothi to marry him. She replied that she was a Madiga and he a Brahman,

and she was not worthy to marry him. He did not accept her refusal, and declining to leave the house, lay down on the veranda.

When Aranjothi’s brothers came home they dragged him away, throwing him into a pit, and themselves lay down in the veranda.

Aranjothi now realized who her suitor was and married him against the wishes of her people.

Aranjothi’s father was now very angry and

cursed her, saying that she should be a star in the northeast. When she asked him if he did not have a blessing also for her,

he replied that after two ages the Kali yugamu would come, and then all would worship her. He then cursed the husband

of Aranjothi also, saying that he should become a star in the southeast, but in compensation he was to be known as a rishi

and worshiped also. His worship, however, does not seem to continue among the people. Aranjothi now in turn cursed the Madigas,

saying that they should always live in poverty, ignorance, and slavery.

[…]

The Brahmans claim that this story is a fabrication made by those who wanted to steal their goddess. On the other hand they

do not deny the truth of the tale, although they turn their backs when it is told. […] The name, Aranjothi, is Dravidian,

while the Brahmans call her by her Sanskrit name, Arundhati.

c)

Other heroes

Although Jambavantha and Aranzodi are the two most significant

names in Madiga historical mythology, kings, generals and heroic soldiers are not absent, as the following two readings show.(n)

J.D.B. Gribble, 1875. A Manual of

the District of Cuddapah.

Madras: Government Press

[p. 288]

A pool in Rayachoty taluk of Kadapa district is called Akkadevatalakolam, or the pool of the holy sisters.

A thousand years ago there lived near the pool a king who ruled over all this part of the country. The king had as his Commander-in-chief

a madiga, or chuckler.

This madiga made himself powerful and independent and built himself a residence on a hill still called Madiga Vanidoorgan.

He at last revolted and defeated the king. On entering the king’s palace he found seven beautiful virgins, the king’s

daughters, to all of whom he at once made overtures of marriage. They declined the honour, and when the Madiga wished to use

force, they all jumped into the pool and ‘delivered their lives to the universal lord’.

Wilber Theodore Elmore, 1915.

Dravidian Gods in Modern Hinduism. A

study of the local and village deities of Southern India.

Hamilton, NY: The Author

[pp

107-109]

There are many myths about Katama Razu. In the worship of Gangamma a Madiga cuts off

the pith post as described [in a note (26)]. The following narrative explains the act.

When Katama Razu was reigning in Nellore, he was engaged in a war. His brothers could not come to help him, so

he sent for Berunaydu, a Madiga king, who at once fitted out an expedition and came to his relief. All the earth trembled

when this doughty king set forth. The gods saw him, and knowing that he was certain to conquer, determined to prevent his

progress. They placed a great log across the road, such a log as no-one had ever seen before, and one that it was impossible

to scale. Berunaydu came to the obstacle, and said, ‘If I can cross this log it will be a great honour to me in the

eyes of Katama Razu, but if I cannot, I must return in disgrace.’ Saying this, he drew his sword, and with one stroke

cut the log in two. His army passed through, and went on to victory. This sword appears to be connected [108] with the one

used in beheading the buffalo sacrifice. Its power is explained as follows. In a previous age Vishnu, seeing that in the Kali

Yugamu men would need much help, called his goldsmith, Visva Brahma, and giving him a lump of gold told him to make four

useful articles with it. The sword was one of the articles. It is to be noticed that the sword was given into the hands of

a Madiga.

The shepherds worship virulu or heroes. Such

personages have many of the characteristics of village deities, but are not female. They are of Madiga origin. The legend

goes on to tell of the origin of their worship.

Chenniah

Baludu, a brother of Katama Razu, was having a terrible war with the people of Karamapudi. He sent to Katama Razu for help.

Katama Razu was in the midst of a war of his own and could not come, so Chenniah Baludu appealed to the Madigas. They came

at once and entered into the battle with great success. At night all the warriors lay down to sleep. In the morning Chenniah

Baludu sent his prime minister to call the Madigas to a feast which he had prepared for all without caste distinction.

The prime minister did not wish to

call outcastes, so he returned after remaining away a sufficient time, and said that the Madigas were bathing. Again he was

sent, and again without going near them he returned and said that they were putting on their botlu, or caste marks. Once more he was sent,

and this time he reported that they were tying on their clothes. As it was growing late, Chenniah Baludu decided to wait no

longer, so, putting their share of the feast on one side, he and his men ate their part.

While Chenniah Baludu and his men were eating, someone came to the Madigas,

awakened them, and chided them for their laziness. They rubbed their sleepy eyes, arose, and came to the feast. Chenniah Baludu

now saw that he had been deceived by his messenger, and explained the matter to the Madigas, inviting them to eat. They did

not accept his explanation, however, and accusing him of making caste distinctions, said they would remain seven days and

fight his battles, but they would not touch his food. Chenniah Baludu now became indignant and saying, ‘If you will

not eat my food, you shall not fight my battles,’ he sent them away.

The Madigas returned to Katama Razu, and when he saw that they had returned without fighting any battles

or winning any victories, he was angry and would not speak to them. The Madigas were filled with chagrin, and saying, ‘We

did not have any part in the battle with Chenniah Baludu, and now we have no part with Katam Razu, so it is better for us

to die,’ they threw their weapons into the air, and baring their breasts were slain by the falling swords and spears.

For this brave act they were immediately admitted into the heaven of heroes.

The viralu [sic] now are thought to dwell in the sacred jammi tree [mimosa suma]. The place is marked by a stone, but the spirits are in the tree, not in the

stone. They are propitiated especially at wedding times, no doubt with the idea that the powers of these heroes will appear

in the offspring. At such times it is common to kill a sheep and throw the blood in the air for the spirits.

d)

Leather work

Reporting on the leather

work of Madigas from any period is scarce, but this essential aspect of Madiga history requires notice. It has been a major

root of their distinctive identity and of their importance for the society they have served. Here, Buchanan provides an account

from the early nineteenth century of the techniques of city tanners from Bangalore, and Chatterton a wider ranging account

of the industry in the Madras Presidency a century later. The fearsome reputation of the conditions in which leather work

in general and of tanning in particular were carried on means that they have rarely been seriously observed and recorded at

first hand. The section ends with a folk song which brings out aspects of leather work and the way these are expected to be

particularly offensive to Brahmins. For an account of the practical and social significance of village leather work, see Chapter

5.

Francis Buchanan 1807. A journey from Madras

through the countries of Mysore, Canara, and Malabar …. 3 vols. London: T. Cadell & W. Davies.

[Vol. I, p. 77] Evidence from Srirangapatna, near Mysore,

Karnataka:

Eddagai and Ballagai division

There are nine ‘tribes or casts’ of which ‘Midigaru’,

tanners and shoemakers, are last: ‘as their own name is reproachful, they are commonly called the Eddagai [left hand]

cast, as if they were the only persons belonging to it’.

[p. 227] Evidence from Bangalore:

Leather is tanned here by

a class of people esteemed of very low cast, and called Madigaru.[…] To dress the raw hides of sheep or goats, the

Madigaru in the first place wash them clean, and then rub each with a fourth part of a kind of soft paste, made of 6 Dudas

weight of milky juice of the Yecuda (Asclepias gigantean), and about 6 Dudus weight (2 456/1000 ounces) of salt (muriate

of soda), and twelve Dudus weight of Ragy Sanguty, or pudding of the Cynosurus coracanus (o), with a sufficient quantity

of water. The paste is rubbed on the hairy side, and the skins are then exposed for three days to the sun, after which they

are washed with water, beating them well on a stone, as is usual in this country. This takes off the hair. Then powder 2 Seers

(1 213/1000 lb.) Arulay Myrobalens, and put them and one skin into a pot with 3 or 4 Seers measure of hot water, where it

is to remain for three days. The skin is then to be washed and dried.

This tanned skin is dyed black as follows: take

of old iron, and of the dross of iron forges, each a handful; of plantain and lime skins, each five or six; put them into

a pot with some Ragy kanji, or decoction of Ragy, and let them stand for eight days. Then rub the liquor on the skins, which

immediately become black.

These skins may be dyed red by the following process: Take of ungarbled Lac 2 Dudus weight (about

13 drams), of Suja cara, or fine soda, 1 Dudu weight, and of Lodu bark 2 Dudus weight. Having taken the sticks from the Lac,

and powdered the soda and bark boil them all together in a Seer of water (68 5/8 cubical inches) for 1½ hour. Rub the skin, after

it has been freed from the hair as before mentioned, with this decoction; and then put it into the pot with the Myrobalens

and water for three days. This is a good colour, and for many purposes the skins are well dressed.

The hides of oxen and

buffaloes are dressed as follows: For each skin take 2 Seers (1 213/1000 lb.) of quick lime, and 5 or 6 Seers measure (about

1 1/3 ale gallons) of quick lime, and in this mixture keep the skins for eight days, and rub off the hair. Then for each skin

take ten Seers, by weight, (about 6 lb) of the unpeeled sticks of the Tayngadu (Cassia auriculata) (p), and 10 Seers

measure of water (about 2½ ale gallons), and in this infusion keep the skins for four days. For an equal length of time,

add the same quantity of Tayngadu and water. Then wash, and dry the skins in the sun, stretching them out with pegs. This

leather is very bad.

Chatterton, A. 1904. Monograph on

Tanning

and Working in Leather in the Madras Presidency. Madras: Government Press

Chatterton identifies the major production: the requirement

of the civil population is ‘confined chiefly to leather-thongs and ropes for the harness of draft cattle, to water-bags

for the country mhote, and to vessels for holding oil and ghee’ [p. 3]. There must also have been big tanneries for

providing for the requirements in harness and saddlery for the horses of irregular troops and retainers of local chiefs and

rulers. By the beginning of the 20th century, in the coastal region many were no longer pursuing ‘their hereditary calling’

[p. 13].

[pp 40-41]

The largest consumption

of leather in the Madras Presidency was for water bags or kavalais for raising water from wells, and for oil and

ghee pots for transportation. There were nearly 600,000 wells, nearly all of them with ‘leather bags and discharging

trunks’, just a few with iron buckets or other devices. The bags were of 10-50 gallon capacity, generally of ‘well-tanned

cow hides’ or sometimes, for very large ones, of buffalo hides. They were semi-cylindrical in shape and suspended from

an iron ring. ‘At the bottom is a hole about 8 inches in diameter which leads into the discharging pipe – a leather

tube 5 or 6 feet long, the open end of which is attached to a rope’. This is ‘the common mhote’ mentioned

above. The ‘very hard treatment which the leather receives from the hands of the ryot’, alternately wet and dry,

seldom or never greased, means that it perishes rapidly. When in use everyday it seldom lasts more than 6 months. ‘During

the latter part of that time it requires frequent repair which is a source of much annoyance to the ryot, as he is entirely

in the hands of the village chuckler; and the latter, knowing that his services are indispensable makes the most of the situation’.

On average, probably each well needs a new bag every year, so perhaps a million hides a year are required. There are also

huge numbers of the spherical oil and ghee pots but they have a long life and are now being replaced by ‘the ubiquitous

kerosene oil tins’. Already by this date they were expected to die out soon.

Articles produced:-

leather straps for wooden sandals; harness for ryots’ cattle, including collars

to which numerous bells are frequently attached; whips for cattle drivers; ornamental fringes for the bulls’ foreheads;

bellows for the smith; small boxes for the barber to carry razors; some places have leather harness to attach heavy coir ropes

to temple cars for drawing them along; ‘drumheads, tomtoms and similar abominations’.

Raw hides are also used by Vettians and Chucklers to produce

all sorts of drums, some huge to be carried on elephants. For small drums, sheep skin may be used. The raw hides are shaved

on the flesh side and dried. ‘Hair is removed by rubbing with wood ashes. The use of lime in unhairing is not permissible

as it materially decreases the elasticity of the parchment’.(q)

H.V. Nanjundayya

& L.K. Ananthakrishna Iyer 1931. Mysore Tribes and Castes. Vol. 4: Mysore: University Press

[p. 163] From Karnataka, they note the Bāla Basava – a Madiga who visits villages

to sing the history of Basava and Aralappa, to the accompaniment of a tamburi, ‘a stringed instrument like

a vīna but without its note gradation’. ‘He is rewarded with doles raised by subscription’. He also

foretells the future. ‘He bears a mudre (an insignia) of Goni Basava (a bull with a saddle)'.

[p.155]

Madigas

‘pay reverence to their patron saint Aralappa’. He established his devotion to Basavaṇṇa,

the founder of the Vīrasaiva movement, by giving him sandals made from the skin of his wife’s thigh. In return

he was allowed to wear the linga. ‘Even now’ he is revered by Madigas on all important occasions, such

as marriage.

That Madigas may be Vaishavites as well as Shaivites, or not really either, has been noted

by Singh (1969) and elsewhere.

Kalikiri Viswanadha Reddy 1989.

An anthropological

study of Telugu folk songs (A case study of Chittoor District, AP). Tirupati: Sri Venkateswara University.

[pp 105-07] An Aram Jyothi song (r)

[Click to find this in Chapter 4, under 'Significant Others': Brahmins)]

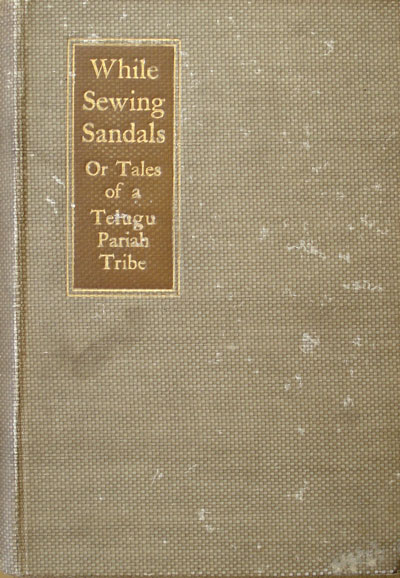

| 'Madigas sewing sandals', late 19th century |

|

|